When the KKK threatened to burn down the house: stories from my stepfather, Bill Jones

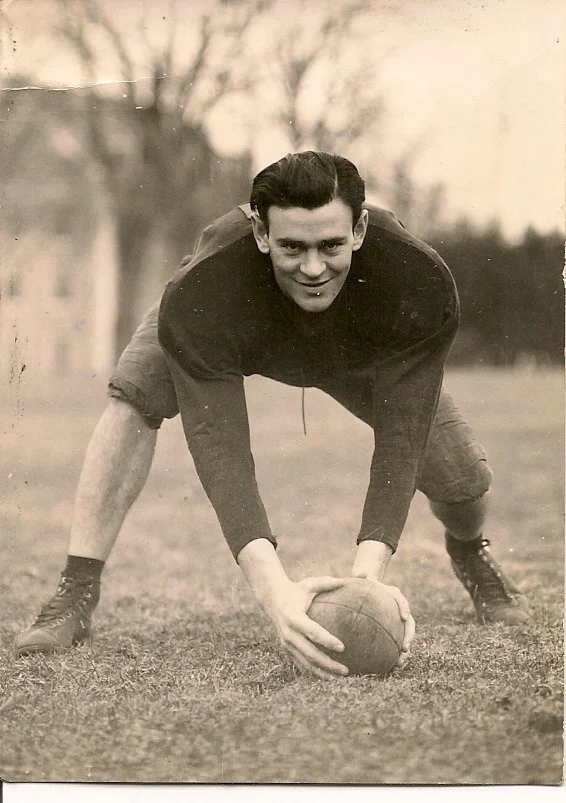

/When I was a really little girl, about four or five, my mother met a really great guy and married him in 1978. The guy was Bill Jones, and he hailed from the state of Alabama. I remember the first time I met him. He came to our house to pick up my mother, and when I opened the door, he said, "Hi!" in his best Southern drawl. He spoke a really peculiar language to me. He said things like, "Did you bump your noggin?" and "Has anyone seen my billfold?" He ate crazy things like black eyed peas and cornbread. He would chop up his over easy eggs (called "dippy eggs" in my south central Pennsylvania lingo) until the yolks were broken, then tear his bacon apart and mix it in with the eggs. And god help you when the Auburn vs. Alabama game was on. Much yelling ensued from the family room.

I didn't know too much about his upbringing in Sylacauga, a small down about an hour southeast of Birmingham. Lately, I've been asking him questions, and the stories he has are gold.

On September 16, 1963, a bomb went off in the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, AL. Four men associated with a Ku Klux Klan group planted a bomb in the basement of the church, ultimately killing four young girls and wounding 22 other people. The governor of Alabama, George Wallace, famously stated "Segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever" and gained national notoriety for his publicity stunt of "Stand in the Schoolhouse Door" when he blocked the admissions entrance at the University of Alabama to prevent two young African American students from registering. After the tragedy in the 16th Street Baptist Church, civil rights activists blamed the bombing on him.

George Wallace standing in the door at the University of Alabama, 1963.

My stepfather, a 20 year old student at Auburn University, decided to write a letter to the Birmingham News expressing his concern over Gov. Wallace and the "stands" he took. The paper printed it on September 18, 1963. The letter reads:

“Alabama Stand” Hasn’t Helped State

During the governor’s election, Sen. deGraffenreid talked to our senior class. He told us that loudmouth threats would only bring trouble. He said the way to settle the segregation problem was through law and order.

Many people talked about all the young people at deGraffenreid’s speeches and said that they couldn’t elect him. Well, this young person will be able to vote next time and so will many other young people.

I have seen what Gov. Wallace’s “standing up for Alabama” has done. He stood right in the doorway of our schools and moved when told to. Very good publicity! In fact everything he has done lately seems to be for publicity. When Huntsville’s mayor openly criticized the governor, he let the local school board settle the problem; and they have had no trouble.

How can Alabama progress when the governor, who is the representative of the people, admits all he wants to do is have President Kennedy defeated in the next election, and then, for example, have to turn right around and ask him to declare Huntsville a disaster area?

I think it’s time for the local school board to take over, call an end to some of the students’ excuse for taking an extended vacation, and time for some of the people of Birmingham to grow up.

BILL JONES, 917 Craddock, Sylacauga

And then the letters started pouring in.

The letters were mean. And violent. And from the tone, my stepfather and his family could tell they came from the KKK. They called him a commie. They threatened to either blow up or burn down the house. Six or seven letters arrived in all.

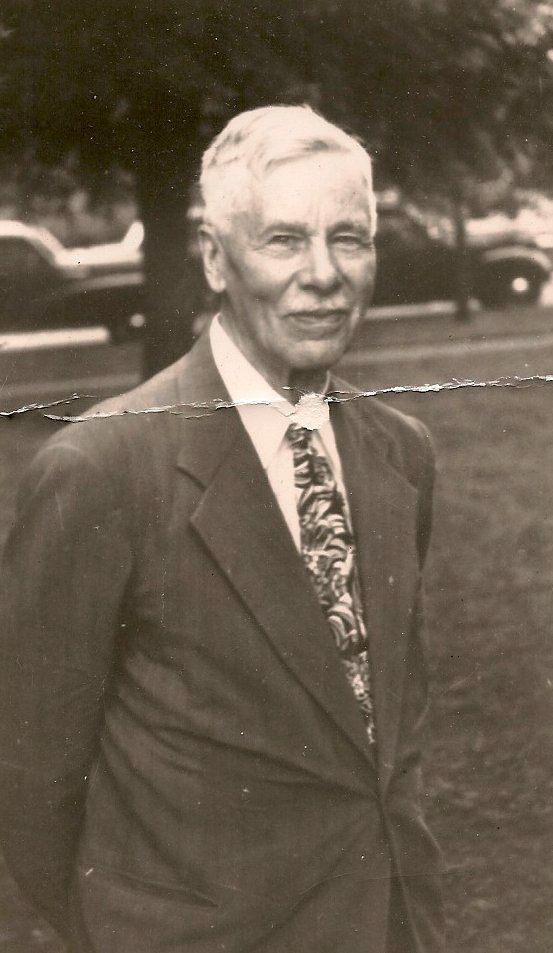

Bill Jones

But the threats were empty, and eventually the attention died down. And Bill's parents didn't give him too much grief about it. The only advice Bill's father really gave him was this: "Next time you write a letter, make sure it doesn't have my address on it!"

Last week, my stepfather had a birthday. He is a humble and joyful person to be around. And we all are so very proud and love him dearly.

Love you to the moon and back, Billy Charles.