The Charlotte News articles: Tom Jimison and the Morganton Women's Ward

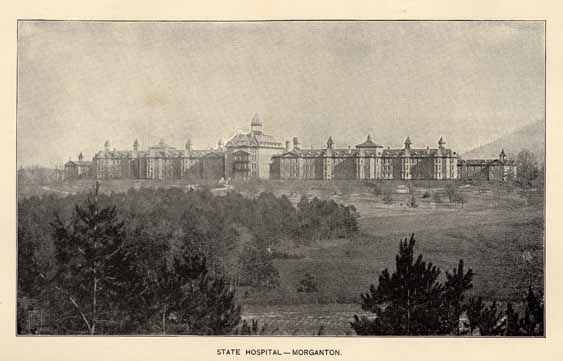

/Discovering the conditions at the Morganton State Hospital only added to my desire to find out more about what happened to Hannah during her stay there. The hospital reports told me some, but I still wanted to find out more on a personal level. I discovered two series of Charlotte News articles about life in Morganton State Hospital: "Out of the Night of Morganton" by Tom Jimison and an exposé on the women’s ward.

Jimison, a prominent lawyer, activist, and former minister, made a name for himself in North Carolina as a labor organizer and reformer. He struggled with alcoholism and worked for the Charlotte News as a freelancer to earn an income. Clark R. Cahow in People, Patients and Politics says, "Jimison's popularity as a preacher and a newspaper man resulted from a combination of fierce mountaineer independence and the ability to relate his opinions, whether on love, loyalty, patriotism, or the events of the day, in an appealing North Carolina dialect that 'rang true' to the native listener and the reader."

In early 1940, Tom Jimison voluntarily checked himself into the State Hospital at Morganton where he stayed for a little more than a year. His doctors suggested he receive treatment for his alcoholism and exhaustion, along with Jimison admitting "a sort of hankering to see how the institution at Morganton was run." In January of 1942, the Charlotte News began a series of 16 articles written by Jimison about his time and treatment there. (Just a side note: I understand these articles were written about 18 years after Hannah's stay. I have no reason to think the treatment changed much in those 18 years. Therefore, I believe what Jimison and the anonymous female author stated can be closely compared to previous decades.)

Right away, Jimison noticed the hospital had the air of a prison rather than a place of rehabilitation: "...the physically ailing are tenderly nursed while the mentally ill are hurried off to public asylums where they are incarcerated like felons and practically forgotten by society." Jimison spent two weeks in the county jail before being admitted to Morganton, a standard procedure of the time. "At best, the present procedure is of a quasi-criminal nature, and the average patient reaches the hospital in Morganton after a sojourn in a filthy jail; and it frequently happens that they arrive in handcuffs in charge of some unsympathetic peace officers. I have seen many arrive there covered with vermin from some county jail and frightened within an inch of their lives. They get off to a bad start. Drat 'em, they should have not gone crazy in the first place."

One of the most horrific subjects Jimison writes about is the women’s ward.

“There was one thing at the hospital that always harried my very soul. It was the screaming of the women. To me the most terrifying noise on earth is the anguished wail of a demented woman. It has in it the pain of perdition, the agony of a broken heart, the cold shuddering fear of a lost soul.”

He recalls an elderly woman who would stand at her window and scream:

“What was going on in her tortured mind? Was she hearing vulgar voices which shocked her sensitive nature with ugly suggestions and indecent proposals? Was she seeing ghosts and goblins and impish apparitions? Was she being haunted and tormented by the recollection of unseemly conduct of the dim and distant past? Or was it Rachel weeping for her children because they were not? Perhaps no one would ever know. Apparently no one cared.”

The anonymous writer of The Women’s Ward at Morganton came from a prominent family and studied at Queens College in Charlotte. In the summer of 1939, she entered Morganton State Hospital due to a nervous condition. At the beginning of each of her articles, the Charlotte News states her identity is known to them, but because of the stigma of mental illness, they have chosen to withhold her name.

Almost immediately, she discovered the horrific condition of the food. The admitting nurse informed her she arrived too late for lunch and the hogs on the grounds ate the leftovers. The patient wrote, “I felt sorry for myself at first, but when I saw the food, my sympathy was all for the hogs.” Jimison also spends a lot of time criticizing the food, describing dishes filled with flies and once even a rat. He also describes a situation where a fellow patient who suffered from itchy sores all over his head would be in charge of handing out bread to the other patients while he scratched. Only when Jimison complained several times and reached the top level of the administration was the patient relieved from his job of serving bread to the tables.

The Woman’s Ward author was placed in the “front ward:” a dark, dismal area where the walls had so much dirt on them they appeared black. Other patients told her she got the lucky ward; the back wards contained women crowded into poorly ventilated rooms and hallways where one bulb hung from the ceiling and the stench of human waste made her gag. Forty women shared three toilets that constantly overflowed; toilet paper was rationed but ran out within three days. Although a tuberculosis section existed, patients who suffered from TB and syphilis mingled together.

Every night the author shook out her bedding to get rid of the roaches infested there. She longed to get outside even for just a short time, but she soon learned the women were never let outside for fresh air; many women were crowded onto a porch that only had five chairs for 40 people, and some women had not set foot outside for decades. The nurses would herd some of the women from the back wards onto the porches and lock the doors, leaving them there for hours. The porch had no bathroom facilities. The author describes a nurse putting a fellow patient in a straight jacket and locking her on the porch for hours on a cold November day.

While at Morganton, the anonymous female patient received only one medical examination. She describes doctors coming through the hallways and barely even glancing at their patients. Jimison, however, speaks highly of some doctors. He does deliver harsh criticism of the attendants and nurses, almost all of whom were completely unqualified, mostly illiterate, and severely underpaid. Patients did a large amount of work cleaning for the hospital, working long hours despite severe illness. The anonymous author describes a woman who “…was about ready to go home. She was doing as much work as she was able to do on the ward but the nurse ordered her to go to the hospital ward to work. She begged not to go, saying that she could not hold up the hospital work. I think that she was going through the menopause. The nurse forced her to go and the inevitable happened. She went berserk, was placed on a back ward and was still there when I last heard of her.”

The hospital went to great lengths to uphold a reputable front while covering up what actually happened within the wards. Nurses and attendants censored patient correspondence and removed anything negative about the hospital. Some letters managed to get out, but many were thrown away. Patients received visitors in a spotless room in the front ward so not to give a negative impression to family members. Any complaints made by the patients were dismissed as “delusions”.

Although Morganton released Jimison and the author of The Women’s Ward, many people, like my great grandmother, Hannah, met their deaths while committed. Jimison writes: “When a patient dies the hospital notifies his family. If they are sufficiently interested and sufficiently able they send for the body. If not the deceased is placed in a cheap, rough coffin, made in the hospital carpenter shop and lined with black fabric from the sewing room, and buried beneath a heavy chain which is supported by concrete posts. Over each grave along these strands of chains is placed a brass tag of identification. Jes’ a patient. One wag gazed at the heavy chains along the rows of graves and exclaimed, “I’ll be damned! They keep us locked up as long as we live and then chain us down when we die.” Reading this, I found some comfort in knowing my family sent for Hannah and buried her in her church graveyard near her home and loved ones.

Both authors spoke vehemently about reform and change for the Morganton State Hospital. I was surprised and touched at how both of them showed such great pride in the state of North Carolina. Jimison writes, “I cannot believe that the people of North Carolina are content to have their sick and helpless neighbors herded in such an asylum, fed on fat back and dried beans, worked like convicts, and then furnished with such a small staff of physicians that many of them cannot have the proper medical attention when wracked with physical pain and suffering.” The anonymous author ends her series of articles saying:

“The people of North Carolina are noted for their goodness and piety. They have ever been leaders in moments to better the sufferings of humanity. I do not believe there is a citizen of this state who, if he were allowed to go through the State Hospital and experience conditions as they actually are, would not come away with the feeling that his fellow man had been betrayed. Certainly it is not the will of the estimable men, our neighbors and friends whom we send to the Legislature, that such conditions exist. The inmates of the hospital are our own people, boys and girls with whom we romped as children, now grown to manhood and womanhood, a neighbor from across the street, a friend from the hills, our own brother or sister, mother or father…Let us have a State Hospital at Morganton that pays it helpers a living wage, a hospital that gives to its patients kindness and understanding, a hospital that rebuilds minds and bodies wherever possible, and that gives to those pitiable incurable patients a haven of refuge and comfort.”

Even though I don’t exactly know what Hannah went through, I can say her three months at Morganton were bleak and dark. And since the hospital offered insufficient medical care, I have to question her cause of death. I will never know. I hope her suffering and death happened quickly. But I know her family dealt with her absence for decades. My father told me once how my grandfather would sit on the front porch and cry, and no one knew why. I have to believe he felt the lack of his mother in his life acutely, and since he came from a generation where the past wasn’t really discussed, his wounds ran deep.

So where am I left with all this? I want the world to know there was a woman named Hannah English Stafford who walked among the western hills of North Carolina. She spent her girlhood in the mountains among the flowering rhododendrons in the summer. She was part of a community where she went to school and church where her father led the choir. She was a daughter, sister, wife, mother, and grandmother many times over. She laughed, cried, and wondered. She held and nursed babies. I don’t know why her family committed her, but I do know she was cheated out of what the best of life has to offer for whatever reason. She has captured my heart and will always be remembered. Rest, Hannah.